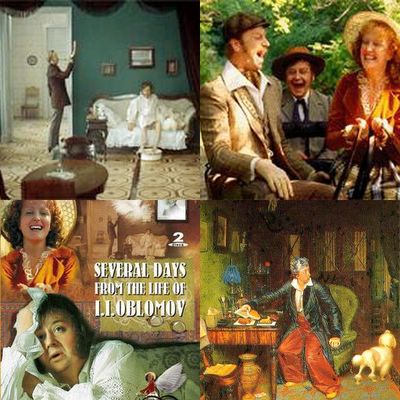

Pictures from Mikhalkov's film plus P.A. Fedotov’s “The Aristocrat at Breakfast”

Pictures from Mikhalkov's film plus P.A. Fedotov’s “The Aristocrat at Breakfast” (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

True heroes tend to be universal, the Honourable Reader might be tempted to agree, but some are more universal than others. The central character of Ivan Aleksandrovitch Goncharov’s one and only masterpiece is the universal archetype for all the selfless non-selfish selves that refuse the modern rat race. Although in their anti-rationalist and anti-modern outlook they are most at ease in XIX century Russia, in fact they persist among ourselves, even in this day and age. The crucial point is, are Oblomovs a good or a bad thing?

Famously, in Goncharov’s novel, the hero needs around one hundred pages just to get out of bed, while this blogger of yours took almost two full days in bed to muster the vital energy to reach for the keyboard.

Oblomov is the laziest hero of Russian literature and has been analysed from every possible approach. I include him in the all-time Top 5 of Russian Male Literary Characters, with Dostoevsky’s Stavrogin (in The Devils); Aliosha Karamazov (in The Bros.); Andrey Bolkonsky (in War and Peace) and Raskolnikov (in Crime and Punishment). While most of them are men of action, almost like role models for existentialist case-studies, who accept the responsibility for their whereabouts and actively design their future with their own hands, Oblomov just is unable to do so.

That dilemma (inaction vs. doing-something-at least) has been occupying me for quite some time, more recently when it was pointed out to me that a French video artist, Martin Le Chevalier, has created an interactive video inspired in “Oblomov”. In that video art game the player (any member of the public) tries to spur the dressing gown-dressed sleeping hero into action (go to the on-line edition of the Moscow Times and look for Anna Malpas’s article on July 8, or use this: http://context.themoscowtimes.com/story/143821/ ). By clicking the mouse the player gets a short burst of action. The hero, interpreted by actor Olivier Bardin, can get up, or smoke a cigarette, or drink wine or make a phone call – but ultimately he will always return to the original sleeping position.

Ilya Ilyich is one of the most sympathetic characters of world literature, a “beautiful soul” if ever there was one, in and outside Russia. At the same time he is a tragic figure, exasperating most readers for his failure to make the final effort to be happy (that is, to follow through the reciprocated love feelings with Olga Sergeyevna).

Agustina Bessa-Luís, a formidable woman writer of my country’s literature, wrote (in 1981) that it was with Oblomov, as a little girl lying in bed with a cold, that she learned “the Russian affection, a kind of Hay Fever without the sneezing”, which she went on to love for the rest of her life.

Auntie Agustina cannot find enough good words to say about the magnificent Nikita Mikhalkov’s film adaptation .(“ Some Days in the Life of I.I. Oblomov”, has been published in DVD with 12 possible subtitles languages by the Russian Cinema Council; and Oleg Tabakov’s performance will never allow you to have any other visual association with the slothful aristocrat.) For Bessa-Luís there is "a kind of cosmic Christology in his way of being, in his self-detachment, which is also direct participation, at a deep level, without selfish desire".

Beautiful things are always sad, defends Agustina (and every Russian folk would shake his head in agreement), and “Oblomov” is in the end a very sad story, full of outstanding comical effects (including the immortal serf-servant Zakhar), but sad. And doubly tragically, I think, because of both the dénouement and because of the arguments that anti-modernization thinkers carved, greedily, from the masterpiece. Agustina even goes as far as talking of “affective intelligence, the climate of domesticity in all its persuasion, almost the nihilist foundation of the human soul” and that this nihilism, “so criticized by some, represents a dédoublement of the universal soul with which we all identify with”.

It’s like we try to extract from “Oblomov” some near-philosophical essay on the meaning of life, and Lesley Chamberlain in “Motherland, a Philosophical History of Russia” has made just that. For her, Goncharov illustrated the fundamental Russian choice of non-selfhood as the basis of ideal community, poking superior fun at the futility of individualistic competitiveness. Oblomov, “in a sleepy labouring towards meaning”, embodied consubstantial, ‘integral’ knowledge for souls rather than aggressive-divisive knowledge for individuals. He is totally unconcerned with Hegel’s essential feature of Western individualism – the difference between individual consciousness and what exists outside it – and lives in an almost pre-Cartesian world, with a bond with nature that is both undynamic and unproblematic. The peaceful way in which Oblomov absorbed knowledge placed him at the centre of an emotional and epistemological idyll. Because Oblomov wanted power neither over nature neither other men, his political existence followed a parallel pacific, non-Western pattern.

The counter-Oblomovian character in the book, a half-German named Stolz (‘pride’ in German) is the active and ambitious Hegelian hero, a mild version of the man-God, the individual in Russian nineteenth-century philosophical mythology whose desire for self-fulfilment was a bid to take God’s place. Goncharov makes his achievement – Western-style happiness (including marrying Olga) as reward for hard work – morally unconvincing.

Oblomov does not engage with the world through reason and could therefore not see modern competitive Western society as the right goal for a good Russia.

In a way, the post-Hegelian voluntarist approaches of what should an individual seek to do in a society committed to progress (including Leninist tragic version) are all “real ugly world” journeys that do not sustain comparison with an Oblomovian un-selfish idyllic communal arcadia. In that respect, reading the book, seeing the film, engaging with what’s all about, is more important now, in the new global selfish competitive village than it was for the Russian intelligentsia.

The personal belief of this blogger of yours is that neo-Oblomovian temptations to go back to good old times (pre-globalisation, welfare models), including in the name of a environment-friendly concept of harnessing individualistic aspirations, will indeed be very strong. But Stolz-like individual hard self-fulfilment awakening in the peoples of Asia will not allow the indulgence of Western laziness.

Of course we are all, at some point, fed up, with this forward hectic pace of our individual lives and would like, so to speak, “to stay in bed”.

True heroes tend to be universal, the Honourable Reader might be tempted to agree, but some are more universal than others. The central character of Ivan Aleksandrovitch Goncharov’s one and only masterpiece is the universal archetype for all the selfless non-selfish selves that refuse the modern rat race. Although in their anti-rationalist and anti-modern outlook they are most at ease in XIX century Russia, in fact they persist among ourselves, even in this day and age. The crucial point is, are Oblomovs a good or a bad thing?

Famously, in Goncharov’s novel, the hero needs around one hundred pages just to get out of bed, while this blogger of yours took almost two full days in bed to muster the vital energy to reach for the keyboard.

Oblomov is the laziest hero of Russian literature and has been analysed from every possible approach. I include him in the all-time Top 5 of Russian Male Literary Characters, with Dostoevsky’s Stavrogin (in The Devils); Aliosha Karamazov (in The Bros.); Andrey Bolkonsky (in War and Peace) and Raskolnikov (in Crime and Punishment). While most of them are men of action, almost like role models for existentialist case-studies, who accept the responsibility for their whereabouts and actively design their future with their own hands, Oblomov just is unable to do so.

That dilemma (inaction vs. doing-something-at least) has been occupying me for quite some time, more recently when it was pointed out to me that a French video artist, Martin Le Chevalier, has created an interactive video inspired in “Oblomov”. In that video art game the player (any member of the public) tries to spur the dressing gown-dressed sleeping hero into action (go to the on-line edition of the Moscow Times and look for Anna Malpas’s article on July 8, or use this: http://context.themoscowtimes.com/story/143821/ ). By clicking the mouse the player gets a short burst of action. The hero, interpreted by actor Olivier Bardin, can get up, or smoke a cigarette, or drink wine or make a phone call – but ultimately he will always return to the original sleeping position.

Ilya Ilyich is one of the most sympathetic characters of world literature, a “beautiful soul” if ever there was one, in and outside Russia. At the same time he is a tragic figure, exasperating most readers for his failure to make the final effort to be happy (that is, to follow through the reciprocated love feelings with Olga Sergeyevna).

Agustina Bessa-Luís, a formidable woman writer of my country’s literature, wrote (in 1981) that it was with Oblomov, as a little girl lying in bed with a cold, that she learned “the Russian affection, a kind of Hay Fever without the sneezing”, which she went on to love for the rest of her life.

Auntie Agustina cannot find enough good words to say about the magnificent Nikita Mikhalkov’s film adaptation .(“ Some Days in the Life of I.I. Oblomov”, has been published in DVD with 12 possible subtitles languages by the Russian Cinema Council; and Oleg Tabakov’s performance will never allow you to have any other visual association with the slothful aristocrat.) For Bessa-Luís there is "a kind of cosmic Christology in his way of being, in his self-detachment, which is also direct participation, at a deep level, without selfish desire".

Beautiful things are always sad, defends Agustina (and every Russian folk would shake his head in agreement), and “Oblomov” is in the end a very sad story, full of outstanding comical effects (including the immortal serf-servant Zakhar), but sad. And doubly tragically, I think, because of both the dénouement and because of the arguments that anti-modernization thinkers carved, greedily, from the masterpiece. Agustina even goes as far as talking of “affective intelligence, the climate of domesticity in all its persuasion, almost the nihilist foundation of the human soul” and that this nihilism, “so criticized by some, represents a dédoublement of the universal soul with which we all identify with”.

It’s like we try to extract from “Oblomov” some near-philosophical essay on the meaning of life, and Lesley Chamberlain in “Motherland, a Philosophical History of Russia” has made just that. For her, Goncharov illustrated the fundamental Russian choice of non-selfhood as the basis of ideal community, poking superior fun at the futility of individualistic competitiveness. Oblomov, “in a sleepy labouring towards meaning”, embodied consubstantial, ‘integral’ knowledge for souls rather than aggressive-divisive knowledge for individuals. He is totally unconcerned with Hegel’s essential feature of Western individualism – the difference between individual consciousness and what exists outside it – and lives in an almost pre-Cartesian world, with a bond with nature that is both undynamic and unproblematic. The peaceful way in which Oblomov absorbed knowledge placed him at the centre of an emotional and epistemological idyll. Because Oblomov wanted power neither over nature neither other men, his political existence followed a parallel pacific, non-Western pattern.

The counter-Oblomovian character in the book, a half-German named Stolz (‘pride’ in German) is the active and ambitious Hegelian hero, a mild version of the man-God, the individual in Russian nineteenth-century philosophical mythology whose desire for self-fulfilment was a bid to take God’s place. Goncharov makes his achievement – Western-style happiness (including marrying Olga) as reward for hard work – morally unconvincing.

Oblomov does not engage with the world through reason and could therefore not see modern competitive Western society as the right goal for a good Russia.

In a way, the post-Hegelian voluntarist approaches of what should an individual seek to do in a society committed to progress (including Leninist tragic version) are all “real ugly world” journeys that do not sustain comparison with an Oblomovian un-selfish idyllic communal arcadia. In that respect, reading the book, seeing the film, engaging with what’s all about, is more important now, in the new global selfish competitive village than it was for the Russian intelligentsia.

The personal belief of this blogger of yours is that neo-Oblomovian temptations to go back to good old times (pre-globalisation, welfare models), including in the name of a environment-friendly concept of harnessing individualistic aspirations, will indeed be very strong. But Stolz-like individual hard self-fulfilment awakening in the peoples of Asia will not allow the indulgence of Western laziness.

Of course we are all, at some point, fed up, with this forward hectic pace of our individual lives and would like, so to speak, “to stay in bed”.

No comments:

Post a Comment