Lost in translations...

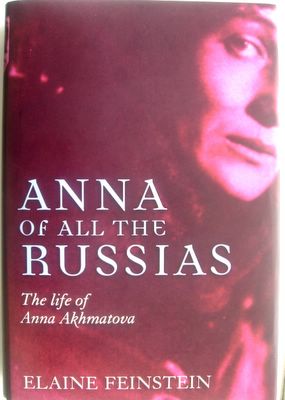

The cover photo is of Ms. Akhmatova in 1922

This biography of Anna Akhmatova, the great female poet of the Russian language, has been in my bedroom for the last couple of months. I read eagerly the first half when it's about immediate pre-revolutionary times, events around 1917 and the first decades of Revolution - and then I lost interest. Russia is a bit like that for me, and for many others as well. Fascinated to understand how Pushkin erupted in world literature, to stare in awe at the very existence of Tolstoy, to try hard to understand what Lenin (and Stalin too) was all about ... but afterwards the viagra-like qualities of Russianness are no longer there. Almost impossible to sustain one's sense of cultural and intellectual arousal when the grey soviet turn-offic reality takes over.

Against my principles I'm going to recommend a book without having read it to its last page. I have a good excuse this time, though. I've just returned from the Círculo de Bellas Artes, a centenary and very active cultural institution of this city, where I have listened to Ms Elaine Feinstein herself, the biographer of Akhmatova and author of "Anna of All the Russias", published in London a couple of months ago.

Ms Feinstein is a poet herself, something I had no idea, and although British and influenced in her early relationship with poetry by the grand Americans such as Elliot and Pound, she confesses feeling now like descending from the Russian poetical tradition of determined women, like Tsvetaeva or Akhmatova. During the seminar she did not use words as such but I got the impression that this descendant of Russian Jews who migrated to England has, with Marina and Anna, "re-discovered" her Russian identity. (More and more we will have to accept with total normality that we carry not one identity (the national or nationalistic one) but an array of identities. The quicker we learn to be at ease with all of them, the better. Some of us refuse to aknowlege a proto-EuropeanUnion identity we now carry with us; others turn a blind eye to XV Century stains of "impure blood" in their lineage; many of us get emotional with former colonies' football national teams..).

Elaine Feinstein realized what Poetry means in Russia and how Poetry was essential in her life (and in the life of Marina Tsvetaeva). She assimilatedd the canon, so to speak, and became -althogh writing in English- a Russian poet herself.

Most of that late morning literary session at the Circulo, organized to commemorate a Spanish poet, ended up dedicated to the phenomenon of translation. (Ms Feinstein is a renowned translator of many Auntie Marina's poems). At some point both another translator who was in the panel and part of the audience were buying the concept that literary translation made by talented writers/poets is literary art itself (some went as far as saying it should be recognized as a separate literary "genre", for goodness' sake!). Well, it's the same old story as with academia texts and literary criticism. Those who write it would like to have a piece of the glory we attach to the "real thing", that is to the product of a creative writer or an original poet. But no way. The translator of Pushkin is not a Pushkin or a less-talented Pushkin but something else. He might even be a Pushkin himself but not as a translator of Pushkin. Did I made myself clear?

Who cares who did translate the poem written in 1917 by Anna Akhmatova starting with "Along the hard crust"?

Along the hard crust of deep snows,

To the secret, white house of yours,

So gentle and quiet - we both

To the secret, white house of yours,

So gentle and quiet - we both

Are walking, in silence half-lost.

And sweeter than all songs, sung ever,

Are this dream, becoming the truth,

Entwined twigs' a-nodding with favor,

The light ring of your silver spurs...

No comments:

Post a Comment